Gravity is one of those ideas that seems unquestionable, a constant presence woven into childhood lessons and scientific explanations. From the moment we learn to walk, fall, or drop a ball, we’re told that a mysterious force deep beneath our feet pulls everything downward toward the center of the Earth. This invisible power supposedly explains why apples fall, why oceans cling to the planet, why the moon orbits, and why planets spin through space. And yet, the more closely we examine this story, the more cracks begin to appear. Gravity, despite its importance, remains one of the least understood and most debated concepts in modern science.

What makes gravity especially peculiar is that no one has ever directly observed it. We see objects dropping, but we do not see “gravity” itself. Instead, gravity exists as a theory — a mathematical framework invented to explain falling motion and celestial orbits. It is presented as fact, yet the deeper you go, the stranger the idea becomes. Scientists admit they cannot explain what gravity truly is. They can describe its effects, but not its cause. Even Einstein replaced Newton’s idea of a pulling force with the notion of curved space, a concept that is just as abstract and untestable.

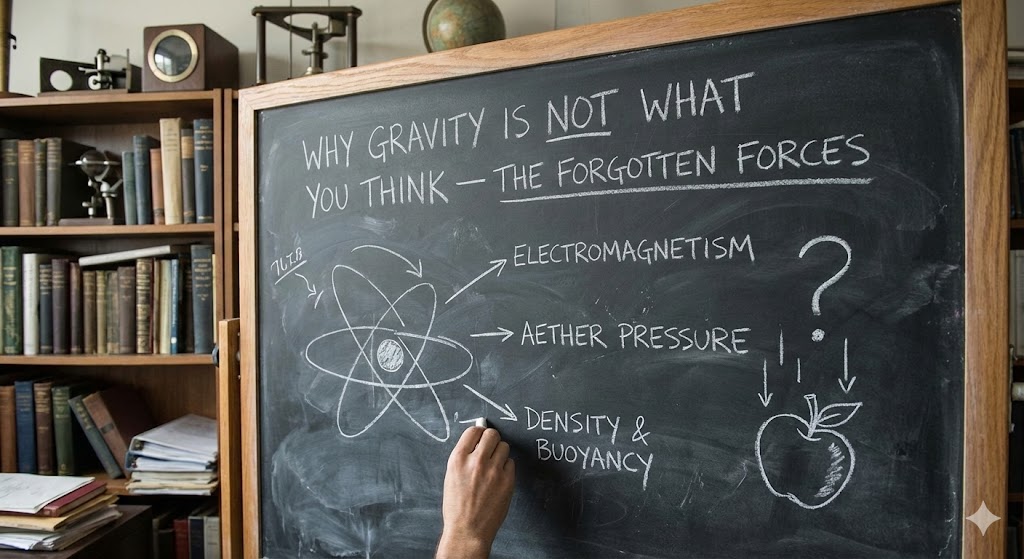

This uncertainty opens the door to an alternative perspective, one grounded not in invisible forces but in simple, observable phenomena: density and buoyancy. According to this view, objects fall or rise not because they are magnetically pulled toward Earth’s center, but because they seek equilibrium in their environment. A rock sinks because it is denser than the air around it. A balloon rises because it is less dense than the surrounding atmosphere. Hot air moves upward; cold water moves downward. Everything behaves according to natural laws of density, weight, and buoyant force — no mysterious force required.

Once you look at the world through the lens of density and buoyancy, the explanations feel intuitive. They match what we see, what we touch, and what we experience daily. We do not need invisible forces bending spacetime to explain why a feather falls more slowly than a stone. We simply recognize that air pushes against the feather more than it does the stone. We do not need gravity to explain why fish remain suspended in water or why helium balloons float. These behaviors follow natural, observable principles.

Yet the gravity model becomes even more questionable when applied to large-scale phenomena. If Earth is spinning at over a thousand miles per hour while orbiting the Sun at a staggering sixty-six thousand miles per hour — and the entire solar system is rocketing through the galaxy at even greater speeds — why does none of this motion affect us? We do not feel it, we do not detect it, and the oceans do not slosh or tilt. The atmosphere remains perfectly calm relative to the ground. Planes flying east or west do not compensate for the alleged spin beneath them. Rain falls straight down. Birds fly without being blown sideways by thousands of miles per hour of rotational motion.

Gravity is invoked to explain away these contradictions. It supposedly holds the atmosphere, oceans, and objects to the Earth so tightly that none of the motion is perceptible. But this explanation feels more like a patch than a truth. When a theory must be expanded repeatedly to cover its inconsistencies, it becomes weaker, not stronger.

The moon adds another layer to the puzzle. According to gravity, the Moon is held in orbit by a delicate balance of attraction and momentum, perpetually falling around the Earth without ever hitting it. Yet the tides on Earth, caused by this gravitational pull, do not behave consistently across the globe. Inland seas, lakes, and ponds remain unaffected by the Moon’s gravity. Large bodies of water like the Mediterranean show hardly any tidal change. Rivers flow against the direction of gravitational pull every day.

The more one investigates gravity, the more it appears to be a mathematical invention designed to preserve the globe model rather than an observable force of nature. Density and buoyancy, on the other hand, require no theoretical leaps. They explain why things rise, fall, float, and sink, without invoking unseen forces or cosmic mechanisms.

Perhaps the truth is simpler than we’ve been taught. Maybe we live in a world where objects behave based on their physical properties, not because they are tethered to an invisible center. Maybe the Earth is not a spinning ball requiring a complex gravitational explanation, but a grounded, stable plane where natural forces operate plainly and consistently.

Gravity, as we’ve been told, might not be wrong — but it might not be necessary. And sometimes the most powerful revelations come from questioning what we assumed was unquestionable. If gravity is not what we think it is, then our entire understanding of the world around us — from the sky above to the ground beneath our feet — becomes open to rediscovery.

You really need to get in an airplane.

You cannot explain the location of the airplane in the sky by buoyancy, and yet there you are. For hours above the low-density air.

Now take a bottle of the flat-earth Kool-Aid you smuggled past security, and pour it from nearly two feet high into a cup. Look at that: straight down, even though you don’t compensate for the 600 mph motion. But by your reasoning, that Kool-Aid should have splashed the guy 300 feet behind you, since that’s how far the plane flies in that 1/3 of a second.

What you are promoting as “common sense” here is ancient and medieval physics, which has been shown over and over to be incomplete and often incorrect. The models developed in the modern era, starting with Descartes, Galileo, and Newton, work much better and can explain not only why there is buoyancy and how it connects to density, but also how fast things fall, why planes stay in the air, and so on.

If you are going to throw out all the science that has been the basis of engineering and technology for 400 years—the time of never-before seen rapid development of the Industrial, Electric, and Information revolution—I think you ought to present an alternative. Present me a theory of nature that is detailed enough to make predictions. I am ready to work with it and test it.