There’s a moment, usually on a clear day near the coast, when the air does something strange. A ship that was hull-down — meaning only the top half visible above the waterline — suddenly appears to float. Or a distant city skyline shimmers, stretches, and then seems to hang suspended above where it should be. Most people glance at it, assume it’s heat haze, and move on.

I used to do the same. Then I started looking into what’s actually happening, and I haven’t been able to look at a horizon the same way since.

The atmosphere is not empty. That sounds obvious, but we treat it like it is when we talk about what we see. We draw diagrams with clean, straight lines connecting the eye to a distant object. We assume light travels the same way through air as it does through a vacuum. Neither of those things is true in practice.

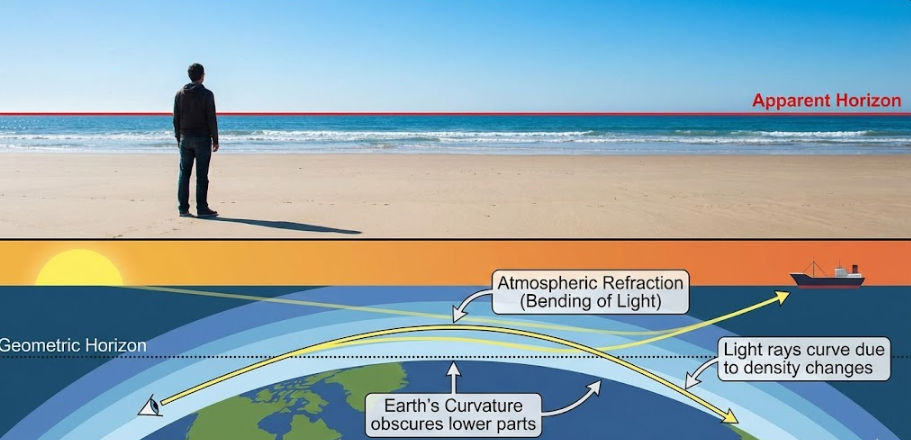

Light changes speed when it passes through different mediums. It slows down slightly in air compared to space, and the denser the air, the more it slows. The atmosphere isn’t uniformly dense — it gets thinner as you go higher, and it varies with temperature, pressure, and humidity at every layer. When light passes through layers of different density, it bends. This is refraction, and it happens constantly, invisibly, in the air around us every single day.

The question isn’t whether it happens. It’s how much, and under what conditions.

Standard atmospheric refraction — the kind textbooks do bother to mention — bends light slightly downward toward the Earth’s surface. This means you can see objects that are technically below the geometric horizon. The visible horizon is typically about 7% farther than the purely mathematical calculation would suggest. Surveyors and navigators have been correcting for this for a long time. It’s a known quantity, a standard table entry, accounted for and moved past.

But standard refraction is the calm, predictable version. What happens at the extremes is a lot stranger.

When there’s a strong temperature inversion — warm air sitting on top of cold air near the surface — the refraction becomes severe. Light traveling along the surface can bend so dramatically that it curves around the Earth’s surface for enormous distances. This is called a superior mirage or, in its most extreme form, a Fata Morgana. The light that reaches your eye has taken a curved path that the geometry of the situation would have made impossible.

What you end up seeing is an image of something that isn’t geometrically in your line of sight. Cliffs that appear to float above the ocean. Ships that appear upside down above themselves. Coastlines from well over a hundred kilometers away. There are documented, photographed instances of the Chicago skyline being visible from across Lake Michigan — a distance where it absolutely should not be. The light bent enough to bring it into view.

Here’s what I kept turning over in my head when I first came across this: we use visual observation as a basic sanity check. If you can see something, it’s there. If you can’t, it’s either too far, too small, or hidden. The atmosphere quietly undermines that logic in ways that are irregular and hard to predict without detailed local weather data.

A researcher in the mid-1800s named Samuel Birley Rowbotham conducted a famous experiment on the Bedford Level canal, observing objects over a six-mile stretch of flat water. He concluded that the results contradicted a spherical Earth. What followed was decades of controversy, repeated experiments, and eventually a clear consensus that he had failed to account for atmospheric refraction — specifically, the tendency of light to bend downward over water surfaces, especially in the temperature and humidity conditions common to English canals.

The error wasn’t in his observations exactly. The objects were where he said they were. The error was in assuming his eyes were giving him a geometrically clean, unaltered picture of the world.

That’s the detail that doesn’t make it into casual explanations of vision and observation. We know about optical illusions — tricks the brain plays on us. But atmospheric distortion is different. The brain isn’t doing anything wrong. The light itself has taken a different path than we assumed. The image is real. The interpretation is where it breaks down.

This matters for any kind of observation that relies on the horizon, on distant visibility, on what should or shouldn’t be visible from a given point. Temperature inversions are common over both cold water and hot desert surfaces. Coastal areas experience them regularly. Any measurement or claim about what can be seen from where needs to account for the atmospheric conditions at the time — not just the geometry.

What does the atmosphere tell us, then, about trusting what we see?

Maybe just this: seeing something is the beginning of understanding it, not the end. The light that reaches your eye has been on a journey through a turbulent, variable, refracting medium, and it’s carrying information that needs to be read carefully. That’s not a reason to distrust your eyes. It’s a reason to ask more questions about what they’re actually reporting.

The horizon is right there. So is everything the air does to it before you see it.