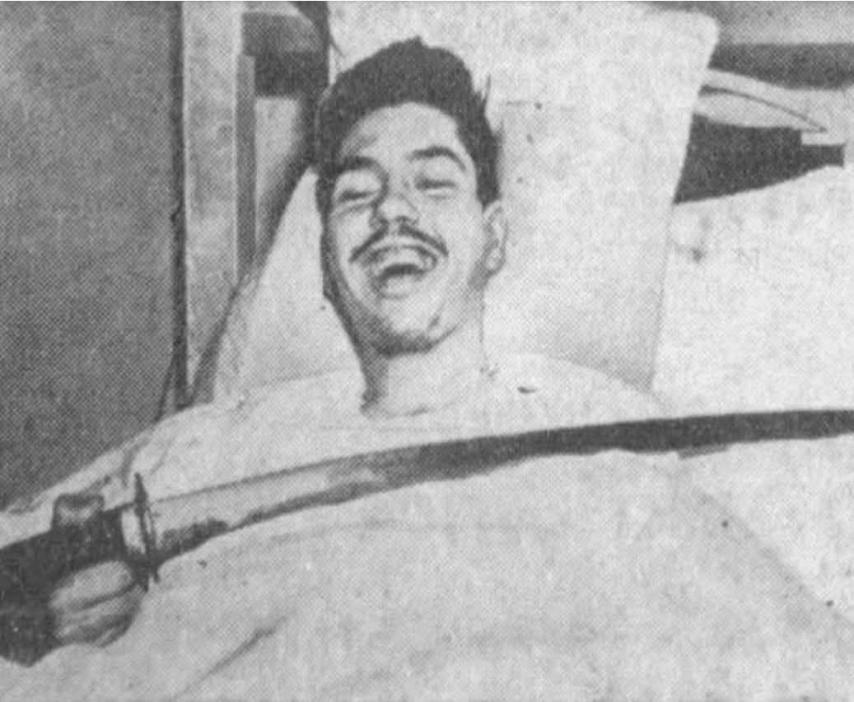

The photo looks almost unreal at first glance.

A young man lies in a hospital bed, smiling—not the polite kind of smile, but the wide, unguarded grin of someone still shocked to be alive. Across his body rests a long, curved sword, the kind people associate with ceremony, tradition, and legend.

But this sword didn’t come from a museum.

It came from Tarawa.

A battle measured in hours, paid for in blood

Tarawa was one of those names that doesn’t need embellishment. Even the most basic descriptions of the battle feel heavy: a small island, a narrow strip of sand, and a storm of gunfire that turned landing zones into slaughter.

The fighting lasted roughly 76 hours, but the cost felt infinite. In that short span, thousands of men were killed, and many more were wounded—sometimes in ways medicine could treat, and sometimes in ways it couldn’t.

Among the wounded was Private John L’Abbe, hit in both legs. The kind of injury that turns movement into a slow, desperate math problem: How far can I pull myself? How long before someone sees me? How long before it’s too late?

He tried to crawl to cover.

Tarawa didn’t allow much cover.

The moment the war became hand-to-hand

Somewhere in that brutal blur—between sand, smoke, and the instinct to survive—L’Abbe was attacked by a Japanese officer wielding a sword.

It’s hard to imagine the shock of that moment. Modern war is often described in distance: rifles, artillery, bombs, aircraft. But Tarawa collapsed distance. It forced men into the ancient kind of violence—close enough to hear breath, close enough to feel impact, close enough to know that seconds decide everything.

L’Abbe was already wounded. Then came deep cuts to his arms.

And still, he fought.

He managed to seize the attacker’s weapon and, in a raw act of survival, used it to kill the officer.

There’s no poetry in that. No clean hero framing. Just a single truth that repeats across every battlefield in history:

People do what they must to live.

$400 on the spot—and an immediate refusal

Right after the fight, a Navy officer reportedly offered L’Abbe $400 for the sword—an amount that would equal thousands of dollars today.

To someone bleeding, exhausted, and shattered, it might have sounded like the easiest money in the world: take the cash, hand over the blade, let someone else carry the weight of it.

L’Abbe refused.

That refusal is the detail that changes the entire story.

Because it suggests the sword wasn’t just an object to him. It wasn’t “loot.” It wasn’t a collectible. It was a physical marker of a moment his body would never forget—proof that it happened, proof that he survived, proof that the line between living and dying can be as thin as a hand gripping steel.

He took the sword with him to the hospital.

And later, when the war was over and the world expected him to become “normal” again, he brought it home.

A trophy—or a reminder you can’t put down

Years later, L’Abbe hung the sword on the wall of his home in Oregon.

From the outside, that can sound like a trophy. And in war, trophies are not rare: flags, helmets, blades, patches—objects taken to memorialize victory, dominance, or revenge.

But “trophy” isn’t always celebration.

Sometimes it’s evidence.

Sometimes it’s memory made solid.

Sometimes it’s a man saying: I need something real to prove this wasn’t a nightmare I made up.

Because here’s what people often miss about survival stories: surviving doesn’t end the event. It only changes where it happens.

The battle stops being a place and becomes a presence.

The sword as a symbol of what war leaves behind

In one sense, the sword represented courage and resilience—an unbelievable moment where a wounded man refused to die.

In another sense, it represented the scars war carves into the living. Not just the wounds in the legs. Not just the cuts on the arms. But the invisible damage: the way the brain replays a moment, the way sleep changes, the way a sound can pull you back into sand and smoke without warning.

If Tarawa was 76 hours of chaos, the aftermath could last decades.

And maybe that’s why the sword stayed on the wall.

Not because it looked impressive—but because it was a permanent reminder that some parts of war don’t stay overseas. They come home quietly, and they hang around.

What do we do with stories like this?

It’s tempting to package L’Abbe’s story as a neat lesson: bravery, grit, triumph.

But the honest version is messier—and more human.

A man was wounded. A man was attacked. A man fought back. A man lived.

Then he carried that moment for the rest of his life.

The sword was not just a relic of combat. It was a symbol of a truth most people never have to face up close:

Survival can be miraculous—and still leave you haunted.

And sometimes, the thing you refuse to sell isn’t worth money at all.

Sometimes it’s worth remembering—because forgetting would feel like dying a second time.