Introduction

When people look out across the ocean, a desert plain, or a large salt flat, the horizon appears as a clean, flat line separating land from sky. For most of us, this moment passes without thought. But for scientists, surveyors, navigators, and observers throughout history, the horizon has never been a trivial feature.

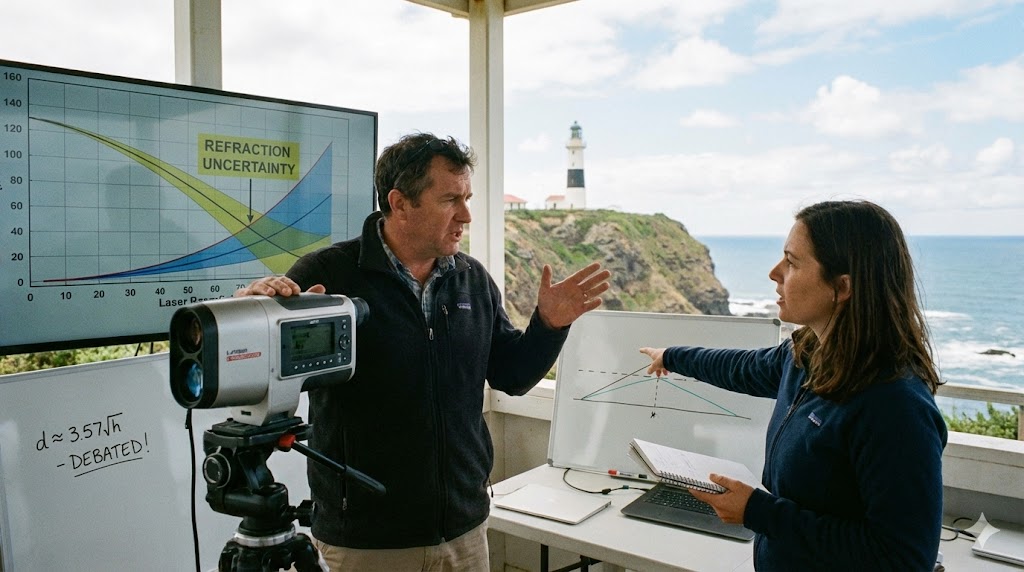

Measuring horizon distance is often presented as a simple geometric problem. In practice, however, it depends on assumptions about light behavior, atmospheric conditions, reference frames, and observation height. This complexity is precisely why debates continue—not necessarily about conclusions, but about methods.

Understanding how horizon distance is measured requires looking beyond simplified formulas and into the actual tools and conditions involved.

The Classical Geometric Approach

The most widely taught method for calculating horizon distance is geometric. It assumes a smooth spherical surface and a straight-line path for light.

Under this model, the distance to the horizon depends only on the observer’s height above the surface. The higher the observer, the farther the horizon appears. This approach works well in theory and is often taught in basic physics and navigation.

However, this model makes two major assumptions:

-

The surface being observed behaves like a perfect geometric shape

-

Light travels in a perfectly straight line

Neither assumption holds perfectly in real-world conditions.

Optical Measurement in the Real World

In practice, horizon distance is often measured using optical instruments rather than equations. These include:

-

Theodolites

-

Surveying levels

-

Long-range cameras

-

Laser-based distance tools

-

Astronomical sextants

These instruments do not measure curvature directly. Instead, they measure angles, alignments, and apparent drop relative to a reference plane. Surveyors typically establish a level reference and observe how distant objects align with it.

This is where discrepancies can appear. Two observers using different instruments, at different heights, under different atmospheric conditions, may report different horizon distances—even at the same location.

The Role of Atmospheric Refraction

One of the most important—and least understood—factors in horizon measurement is atmospheric refraction.

Light does not always travel in a straight line. Changes in air density, temperature, and pressure can bend light downward or upward. Over long distances, this bending can significantly alter what an observer sees.

In some conditions:

-

Objects beyond the expected horizon remain visible

-

Distant structures appear elevated or compressed

-

The horizon itself appears closer or farther than predicted

Because atmospheric refraction is variable, it cannot be treated as a constant. This introduces uncertainty into any measurement that assumes fixed optical behavior.

Historical Observations and Navigation

Before modern equations existed, navigators relied on direct observation. Sailors, desert travelers, and astronomers used stars, landmarks, and horizon alignments to estimate position and distance.

Historical records show that navigators often trusted what they could observe consistently, not abstract models. This does not mean they rejected geometry—but they understood its limits.

Even today, maritime navigation still relies heavily on visual horizon cues combined with instrumentation, not formulas alone.

Why Disagreements Continue

Disagreements about horizon distance do not usually arise because of ignorance. They arise because different people emphasize different aspects of measurement.

Some focus on:

-

Mathematical models

-

Idealized conditions

-

Predictive formulas

Others focus on:

-

Optical observation

-

Repeatable experiments

-

Environmental variability

When these perspectives collide, it can appear as if one side is denying established science. In reality, the debate often centers on how much uncertainty is acceptable when theory meets observation.

The Difference Between Models and Measurements

A model is a simplified representation of reality. A measurement is an interaction with reality itself.

Models are extremely useful, but they are not reality. Measurements are influenced by tools, conditions, and interpretation. Problems arise when models are treated as unquestionable truth rather than approximations.

In horizon measurement, this distinction matters. A model may predict a certain distance, while observation suggests something different. Resolving this requires investigation—not dismissal.

Why This Topic Still Matters

Horizon measurement is not just a philosophical issue. It affects:

-

Long-range surveying

-

Navigation accuracy

-

Optical system design

-

Remote sensing technologies

-

Atmospheric science

Understanding its limits improves accuracy rather than undermining science.

Conclusion

The horizon is one of the most familiar features of our world, yet measuring it accurately remains surprisingly complex. Geometry provides a useful framework, but real-world observation introduces variables that cannot be ignored.

Discussions around horizon distance persist because they touch on a deeper issue: how we balance mathematical models with empirical observation. When handled carefully, this debate strengthens scientific understanding rather than weakening it.

True progress comes not from silencing questions, but from refining how we measure the world around us.